Dual-Arm Grasp Dataset Generator

Abstract: While single-arm robotic grasping has seen massive datasets and benchmarks, dual-arm manipulation remains data-scarce. This post details my implementation of a pipeline that transforms single-arm grasp data into verified, force-closure dual-arm pairs. By adapting the logic from state-of-the-art research for cluttered, small-object scenarios, I aim to enable learning-based approaches for coordinated bimanual manipulation.

The Motivation

I recently read the DG16M paper, which presented a massive dataset for dual-arm grasping. It was an inspiring piece of work, but as I dug into the methodology, I noticed two specific constraints that I wanted to overcome:

- The "Large Object" Bias: DG16M focused primarily on large objects (tables, boxes, bins). Because the objects were huge, collision avoidance between the two arms was trivial—simple distance pruning worked because the arms were naturally far apart. I wanted a system that could handle smaller objects, where the arms are forced into close proximity, making collision management critical.

- Model vs. Scene: DG16M generated grasps using DexNet as a base, which relies on clean 3D object models. I wanted to build my generation pipeline on top of GraspNet-1B. This dataset provides dense grasps in cluttered, real-world scenes captured with RGB-D cameras. By building on this, any network trained on my dataset can learn directly from depth images rather than requiring perfect CAD models.

System Overview

The goal is straightforward but computationally heavy: Take a scene full of valid single-arm grasps and find every combination of two grasps that results in a stable, collision-free dual-arm hold.

The pipeline I built moves through four distinct phases:

- Preprocessing: Cleaning up the noisy GraspNet-1B data.

- Pairing: The combinatorial explosion of matching left and right hands.

- Pruning: Geometric checks to ensure the robots don't smash into each other.

- Verification: The physics math (Force Closure) to ensure the object doesn't fall.

Grasp Representation

Before diving into the pipeline, it's important to understand how grasps are represented. Each parallel-jaw grasp is encoded as a 17-dimensional vector:

where:

- : Grasp quality score from GraspNet

- : Gripper opening width (meters)

- : Gripper finger height

- : Approach depth

- : Rotation matrix (9 elements, flattened) defining the gripper orientation

- : Translation vector (grasp center position)

- : Object ID

The rotation matrix defines the grasp frame where x is the approach direction, y is the grasp axis (from jaw to jaw), and z completes the right-handed frame. The gripper jaw endpoints are computed as:

Phase 1: Cleaning the Data (NMS)

GraspNet-1B is fantastic, but it provides too many grasps. A single good grasp point might have hundreds of slightly varied orientations annotated around it. If we try to pair every single one of these, the computation time grows quadratically ().

To solve this, I used Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS). We calculate a distance metric between grasps that combines both their translation (position) and rotation (orientation):

The rotational distance is computed using the geodesic distance on the rotation manifold:

This gives us the angle of rotation needed to align the two grippers. With as a weight factor, we balance translational and rotational components. If two grasps are physically too close (within 3cm) and oriented similarly (within 30° or radians), we keep the one with the higher quality score and discard the other. This drastically reduces the search space while preserving grasp diversity.

Phase 2: The Pairing & The "Small Object" Problem

For an object with valid single-arm grasps, the number of possible dual-arm pairs is . For 500 grasps, that’s over 124,000 pairs to check.

This is where my implementation diverges from methods that focus on large objects. When grasping a small object (like a mug or a drill), the two grippers are dangerously close to each other. We need rigorous geometric pruning before we even think about physics.

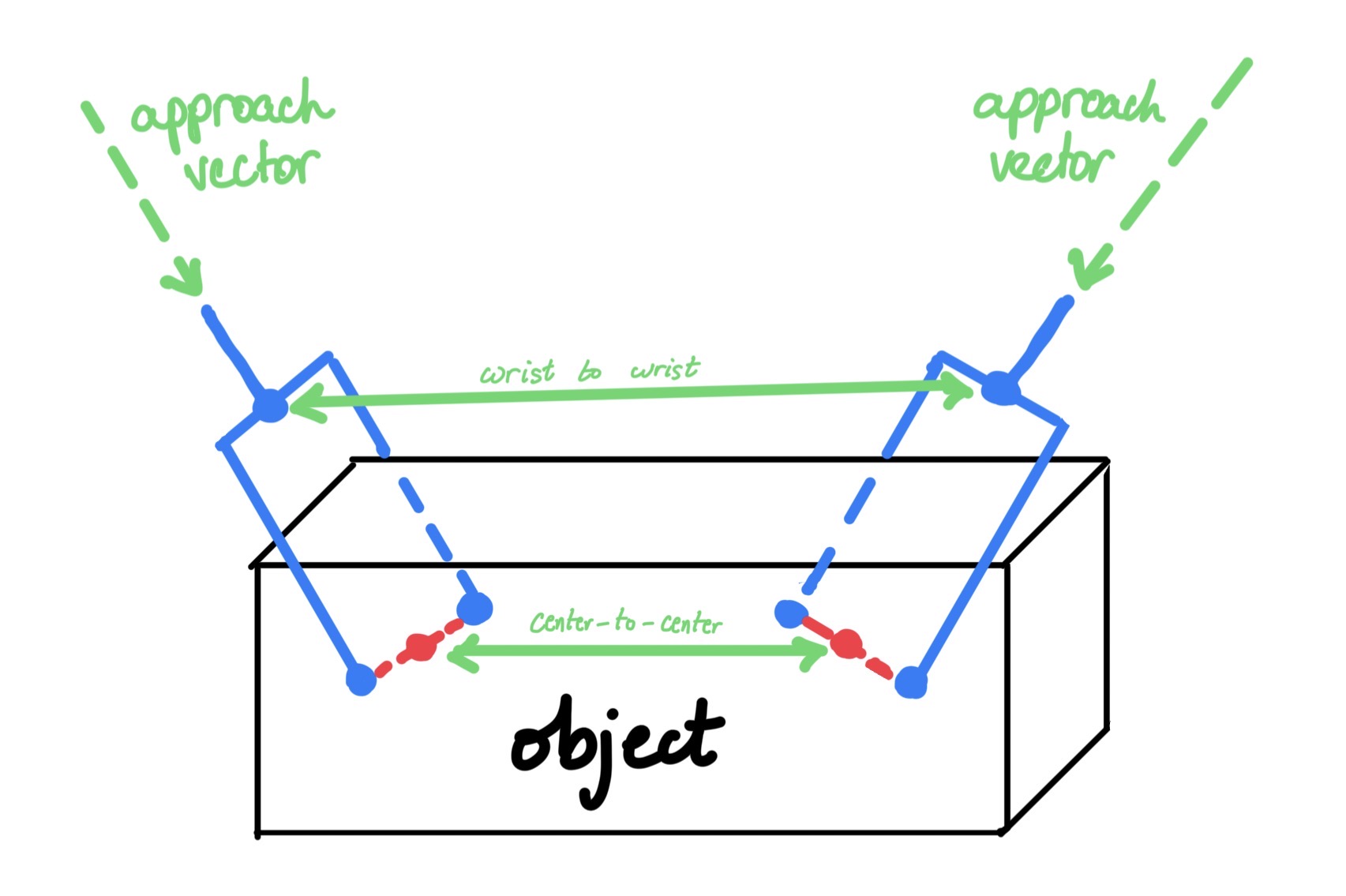

I implemented three specific pruning criteria:

1. Center-to-Center Distance (): This ensures grasps are sufficiently separated. The metric incorporates an axis alignment penalty:

where the axis distance penalizes parallel grasps:

When (parallel grasps), and provides no penalty reduction. When (perpendicular grasps), and provides maximum penalty. This is crucial because parallel grasps cannot resist torques about their common axis—a fundamental limitation in achieving force closure.

2. Wrist-to-Wrist Distance (): We project the gripper position backward along its approach vector to simulate the wrist/arm location:

where m and is the approach direction (first column of ). Then:

If the wrists are too close (< 0.1m), the robot arms will physically collide.

3. Threshold Selection: A pair is retained only if:

with primary thresholds m and m. If no pairs pass, we fall back to m to ensure we get some candidates.

Phase 3: The Physics (Force Closure)

Once we have a geometrically valid pair, we have to answer the most important question: Will it stick?

This is determined by Force Closure—the ability of the grasp to resist arbitrary external wrenches (forces and torques).

Step A: Finding Contact Points

We can't assume the gripper touches the object exactly at the center. I use Signed Distance Functions (SDF) to trace a "line of action" from the gripper jaws.

For each gripper jaw, starting from the endpoint , the line extends along the grasp axis:

The SDF encodes the distance to the object surface, where means the point is inside the object. Contact occurs at the first zero-crossing along the line:

For a dual-arm grasp, we compute four contact points: from gripper 1 and from gripper 2.

Step A.5: Surface Normals and Grasp Maps

Once we have contact points, we need surface normals. The normal at a contact point is the normalized gradient of the SDF:

Critical detail: The normals must point inward (toward the object interior) for the contact model to work correctly.

Now comes the grasp map construction. For each contact , I construct a contact frame with rotation where are tangent vectors spanning the contact plane. The grasp map relates contact forces to object wrenches via the adjoint transformation:

where the adjoint is:

and is the skew-symmetric cross-product matrix. For point contact with friction, the basis matrix is:

The combined grasp map for all four contacts is:

A necessary condition for force closure is . If this fails, we immediately reject the grasp pair.

Step B: The Optimization

For a dual-arm grasp, we have 4 contact points (2 per gripper). We need to determine if there exists a set of contact forces that can balance out gravity and external disturbances without slipping.

This is formulated as a Second-Order Cone Program (SOCP):

The friction cone constraints encode Coulomb friction: tangential forces (in the contact plane) must not exceed times the normal force. These are second-order cone constraints—hence SOCP rather than standard linear programming.

The external wrench represents gravitational loading:

where I use actual object mass to test robustness. I used a friction coefficient of 0.3-0.4 (typical for rubber/plastic) and N.

A grasp achieves force closure if:

where is my convergence threshold. The optimized forces represent the contact forces in the contact frame, which I transform back to the object frame for visualization.

Results and Conclusion

The output of this pipeline is a set of verified dual-arm grasp configurations, scored by their ability to resist external forces.

By shifting the base data from DexNet to GraspNet-1B and implementing better collision detection, this generator allows us to create datasets for cluttered scenes containing small objects. This can be used toward training neural networks that can look at a messy table via a depth camera and decide how to use two hands to pick up an object safely.

References

- GraspNet-1Billion: Fang, H., et al. (CVPR 2020)

- DG16M: A Large-Scale Dual-Arm Grasp Dataset